|

| Chopping in the sunshine, what a wonderful day |

While I was in Rotorua I had the extreme good fortune to get to train some with Kyle Lemon, of the STIHL Timbersports New Zealand national team (on stock saw in https://youtu.be/36rmtxWOQCI?t=18m41s ). I first got to know Kyle when we were preparing and shuttling rounds for the Rotorua Axemen’s Carnival, and had some good conversation about woodchopping and Timbersports as I rode with him on trips in his truck. At the Carnival, I then borrowed a pair of chainmail socks from him, and he came over to watch my chop in my second H-chop event. He must have felt pity on (or seen potential in) me, because he later offered to give me tips if I would come over to his house the following week. I gladly accepted, and for my last two months in Rotorua, every afternoon that we were both available I biked the twenty kilometres up along the lakeside to his place. The first half was on a wonderful bike path running parallel to the old railroad tracks, and I got to know every stretch and shortcut of the route. Once I broke my chain halfway there, but, Kiwis being the nice people they are, I was soon able to hitch a ride the rest of the way. As a serious axeman, Kyle had a dedicated area in his backyard. H-chop stands, a V-chop stand, and even a short springboard setup were all set in a concrete pad, next to stacks of leftover rounds to practice on and a pile of chopped halves of round blocks to split for firewood. His son competes in the U-16 chops (he is nine), and sometimes chopped in the stand next to me, displaying his superior technique, though he usually was riding his bike around and over the nearby dirt piles. Occasionally Kyle would also do a few practice chops while I was there, showing why he is on the national team as he blazed through logs at incredible speeds, massive chips sent flying (He makes up for not being as big as Jason and the others by being very quick and precise). Kyle works full-time as a police officer, yet still carves out the time to keep up with his training and remain competitive. He also puts his axeman skills to practical use; one afternoon after an especially blustery day I came over to find him industriously clearing out a tree that had fallen nearby to block half the road. Kyle also always gave me a ride back into town, and we would chat in a way I couldn’t while winded from chopping.

|

| Kyle chopping at the Rotorua Axemen's Carnival |

For the

most part, Kyle let me borrow one of his older and heavier competition axes to

train with (although once he let me do a few chops with a brand new axe that he

was ‘seasoning’ before using it in competition). This axe held sentimental

value, as he had gotten it from David Bolstad, whose name was etched on the

head. David and Kyle grew up chopping together, and the former went on to win

five STIHL Timbersports Individual World Championships before he suddenly and tragically

passed away as he walked off the field after winning yet another woodchopping

competition in 2011. Himself the son of champion axeman Sonny Bolstad (both of

whom have championship events named after them at the Rotorua Axemen’s

Carnival), his own son (now 13) carries on the woodchopping tradition.

|

| David Bolstad's axe that I got to use |

But as for

the training! Kyle bemoaned on a few occasions that we had not chanced to meet

up earlier. He said he could make me as good as Nathan “Bucket” Waterfield and

competitive on the US STIHL circuit if we had a year to train together, and it

was a shame I hadn’t found him immediately to maximize my 5 months in Rotorua. We

decided that the limited time we had would be best spent in honing basic skills

and building up my technique before I tried to go for speed (Please feel free

to skip to the last four paragraphs of this post if you don’t want to read about

the technical details of going through an H-chop). For simplicity's sake, I’ll

walk you, dear reader, through an H-chop (which we concentrated on) as though I

were Kyle instructing Nathanael. Any errors I make as such are my own, and due

to my mis-remembering rather than a lapse in Kyle’s teaching. Please discuss any

techniques you see here with a qualified captain or coach; in woodchopping I am

an amateur in the true sense of the word, “for the love of it”, whatever the

‘19s may think.

First,

select a round from the stack. It is good to practice on all the different

diameters you expect to chop to know how to pace yourself and structure your

pattern of hits for each. For training now, mostly use 14” rounds to practice

on a medium size, although you can chop 15” and 16” rounds when you are feeling

ambitious, or a 12” or 13” round when you are feeling tired and only want a

smaller chop to finish off the evening [remember that a 12” round is

significantly less wood than a 12” square].

Second,

prepare your chosen round. Slice and peel off the industrial grade cling-wrap

that has been keeping the round moist. Set the round in the H-chop stand, using

a maul (or a rigger when you are actually at a meet) to firmly set it onto the

spikes on one side and lock it in with the swivelling spikes. When placing the

round on the stand, take a look at the end-grain and decide whether you want

the harder wood, where the growth rings are closer together if the round is not

radially symmetrical, on the top or the bottom - whether you want the

marginally more difficult section of the round block to be cleared out earlier

or last. Next, find and mark the point on the round block in the centre of the

stand (I cheated and marked this spot with a log crayon on the stand for later

reference). For the most part you will want a V about the diameter of the log;

on harder wood, like gum [Eucalyptus], you may want a narrower V to remove less

wood, but pine is soft enough for the full width. On a 14” block, holding the

tape measure at 14”, centre the 7” on the earlier marked centre of the log.

Then shift the measure between ½” and 2” toward your dominant side, where you

will start your drives (I usually marked a 14” at 8” drive-side and 6”

chip-side). This offset will make sure your drives overlap and your chips

connect; the variance in offset is based in part on how well you will be able

to keep your line when chopping, 1” offset of the V on each side of the block

is usually sufficient.

Third,

having drawn a line along the top of the block and marked the centre, draw your

Vs. Start with a light, straight line between the chip sides of each

measurement (my left looking down over the block). Next draw in the drive

lines, at the same angle as the chip line so the points are offset horizontally

about 2” and share about 3” of chip line. This gives a bit of leeway when you

get to the centre of the block if you have veered inside of your lines, to

ensure that all the fibres are still severed and the halves will break apart.

What you really do not want is for the points of your Vs to switch sides and

force you to sever the halves on a chip. Sometimes, on older rounds that wave

gotten a thin film of slime the log crayon doesn’t really take and you have to

scrape them with a rigger and follow the marks you can make as best you can,

but on dry blocks you can draw more precise lines. With the most precise lines,

you want to actually make them slightly convex curves, as I will explain later

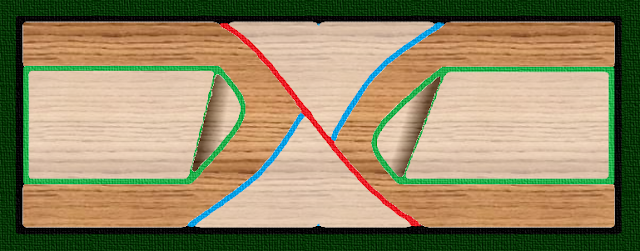

(see the below image).

|

| Figure 1) Diagrammed block, looking down Note the angle of the footholds, and how the edges of the V curve in |

Fourth,

chop your footholds (it is entirely too difficult to balance atop a smooth

round). You want to make them large enough to securely stand and rotate on, but

not overly long, as chopping into your footholds is an automatic

disqualification in competition (removing part of your chopped wood before time

starts). You generally chop down 2” or 3” deep to get a wide enough platform to

position your feet for chopping (because the Vs are offset, the footholds can

be a bit longer on the chip side, but I generally had a tight squeeze against

the drive side when I rotated to the chip. I ended up often having to

consciously hang my heels out over the edge rather than my toes. Although I

always wore chainmaile socks, they don’t have the blunt force resistance of

Dartmouth’s robot boots). This chopping is done with a rigger, an old

competition axe that is no longer even good for practice, but still serves a

purpose. When you have the knack of it, generally choking up on the handle, you

can chop out your footholds and shave them down smooth in only a few strokes.

Fifth, you can finally mount the block and position yourself to chop. You always want your feet to be pointing at the same angle as the line you are cutting, with your shoulders perpendicular to it and your head straight so your body is square and directly behind the path of the falling axe. Keeping your feet, shoulders, and head aligned helps your sight along the axe’s path and chop precisely on your lines. It is helpful to have someone watching you to remind you to keep square, or even to video yourself for later reference (especially if you tend to get sloppy about it, as I did).

Sixth,

either on a “Competitors, on your marks, three. . .two. . .one. . .GO!” or a

“Handicap, one. . .two. . .three. . .” you can finally begin chopping for real!

Try to stick to your pattern while chopping to maintain efficiency of cuts.

Each blow should be aimed at severing new wood fibres, or chipping out already

severed sections to expose more wood. Though sometimes unavoidable, repeating a

chop in the same place can cost a second in a sport where results can come down

to a tenth of that. Similarly, set your pattern to cover the most new wood with

each hit, using the full width of the blade rather than overlapping hits by as

much as half with the previous hit. This comes down to depth perception and

muscle memory; when you are starting out practicing it can be helpful to

dismount the block after a hit, before pulling your axe free, and note how

closely your perception of how low you hit matches with the actual axe

placement (I tended to not reach far enough down). With a 7 ½” wide axe blade

it should only take a pattern of two drives/four hits to sever the width of an

11” block, allowing about an inch of steel to hang out on the top and bottom,

and to overlap in the centre. For larger blocks you’ll want to use a three

drive pattern/six hit pattern, evenly spacing the heights of your hits. Even on

a six hit pattern, you’ll need to start with a four hit pattern until the top

wood is cleared out and you have established a line of sight for your hits on

the bottom wood, ideally in about two or three sets. Whatever the number,

proceed in a circle as you chop; drive top, [drive middle,] drive bottom, chip

bottom, [chip middle,] chip top, repeat circle (as opposed to the drive top,

drive bottom, chip top, chip bottom pattern I have noticed some axemen in the

States follow). Repeat a misplaced hit if you have to, but try to keep the

rhythm going. Each chip (hit) should take a chip (piece) off the face of the

block and expose deeper wood to take out on the next circle. Within a few sets,

drawing an inch of steel out the top of the block, you should notice you have

pretty much severed the top wood in your V, and can move on to a low pattern of

the middle and bottom wood. Once the middle wood is also removed you can move

to a few alternating strokes on the bottom wood, and finish a V with a line of

hard drives to ensure you have severed the fibres on that side. Repeat this

whole process on the other side of the block. If done correctly, the finishing

lines of drives on each side will connect (or at least be close enough that

more than enough fibres are severed and the connecting piece can pull apart

lengthwise), and your block will fall neatly in twain. You’ll be able to feel

how close you are by how much the block shifts with each hit, and customize

your final few hits to this.

Body

positioning is very important for maximizing power as well as accuracy. You

should start a chop in position, waiting on the block for your “go” or handicap,

lined up with your drive line and with the blade of your axe lightly resting on

the top wood. Your hit is allowed to land as soon as time starts, so about a

second beforehand you can lift your axe and have it falling with the signalling

syllable. You will be starting with a drive, on your dominant side, with your

dominant hand (my right) further up on the axe handle and guiding it. Like with

batting baseballs, usually your dominant hand in woodchopping is also your

writing hand, but this is not guaranteed and you should try a few swings with

your hands switched to see what is most comfortable. As you raise your axe,

your dominant hand should slide up the handle to right below the head (and

indeed I barked my knuckles a good many times on the base of the head). At the

top of your swing your axe should be above, but still slightly in front of you;

The power in your stroke comes from the momentum of the head from gravity and

pulling down on the axe, there is no advantage to a huge wind-up with the axe

far behind your head. As you begin your downward stroke, your dominant hand

should slide down the handle, reaching your non-dominant hand right before the

head strikes. As it drops, your dominant hand should push the axe head slightly

out away from you, lengthening its arc and speeding it up, as the non-dominant

hand pulls slightly back to whip it around. Keep that top hand loose and let

the axe follow its path; clenching both hands together at the bottom of the

handle may pull the axe slightly off course and cause you to miss your line,

just like how gripping a pencil too tightly will draw a crooked line. At the

same time, you should add power by bending your knees and dropping your hips

down and back (the affectionately named “butt pop” among Dartmouth Woodsmen).

|

| At the top of your swing the axe is still marginally in front of you |

|

| Slide your dominant hand down the handle, and butt pop! |

It is

always valuable to keep the shapes of your chop in mind; the shape of the block,

and the shape of the cut you are making in the wood. The blade of your axe is

curved, so a line of chops where the horns of the axe overlap only by an inch

or two leaves at those overlaps small triangles of uncut wood. Also, you want

to try to hit the curved face of the round block close to perpendicular, which

requires a slight modification of your swing to sever the full bottom and full

top wood. For getting that bottom wood you will want to keep your hands further

out in front of you so at the bottom of your swing, rotating your hands further

forward, you can reach around and wrap the axe to get at the bottom, your axe

handle ending up almost vertical. To contrast, to chop the top wood you’ll pull

your hands closer to you as you finish the swing, ending with your hands right

down between your legs, your elbows near your knees and your axe handle only a

bit above horizontal.

Once you

are practiced enough to hit exactly where you intend, due to the shape of the

axe blade you will need to start rolling in the face of your cut. (Think of

your block in three-dimensional space; the long axis of your block on the X,

the horizontal short axis on the Y, and vertically on the Z.) Your axe is one

of the simplest machines, a wedge, and as a wedge you cannot perfectly chop a

plane (for this you’d want a woodworking broad-axe). If you try to repeat a

chop in an identical plane, the bevel of your blade will hit before the edge of

the blade, causing your blow to skip. The trick then is to place every deeper

hit on a slightly greater angle to the x-axis, starting off on a shallower

angle and finishing almost chopping square into the centre, so that the final

face is faceted and curves in [see Figure 1]. This brings you back to your

footwork; as the chop comes in at the angle your feet are at, you can fine-tune

the former by adjusting the latter. An ideal face of a cut will be a smooth

transition of facets; it is sloppy and less efficient if there are large

‘steps’ in the face where you kept missing your line to the inside. Failing to

keep to your line on the inside will also cause you to bottom out on your V

before you reach the middle, and force you to either go back and try to cut in

at a steeper angle (and likely skip your axe a lot trying to restart cuts at

such a slightly different angle) or to baseball your way through, driving

straight perpendicular without any chips. When the professionals practice

chopping they are dissatisfied with any hits more than about an eighth of an

inch inside the line of the previous hit.

Congratulations!

You have now chopped through a horizontal log! Work on getting your hits

precise and rhythmic, then build up speed, and before you know it you’ll be

sailing right through in no time at all!

When I

showed up for one of my last practice sessions, Kyle explained to me that he

had noticed a bit of a dent in the axe I usually used, and in attempting to

hammer it straight a sizable chip had just broken off in the centre of the

blade. Every cloud has a bit of a silver lining, however, and that chip in the

blade left an obvious reference mark on the cuts it made, so going back to the

cut faces of the block when I had finished I could easily tell where exactly

the axe was for each cut and how much overlap my middle hits had with my top or

bottom hits. This can be seen on a less prominent scale with any small

imperfections there are on the edge of an axe, though, there is no need to seek

out chips.

There is no

better practice for chopping competitively than chopping practice blocks. It

can be expensive and/or labour intensive to acquire as many fresh blocks a week

as are needed for a rigorous practice routine, however. With saws, at least you

are only using up a few inches of wood with each cut. One way to go about practicing

chopping if you are limited on wood is to make single cuts, to stand behind a

log and shave off an inch at a time at a 45⁰ angle as if it

were a single side of a V. This allows you to practice accuracy and get a feel

for the axe in wood, even if it doesn’t practice you in switching sides and

other chopping aspects. For training the movements and weight, you can stand on

a large tyre and hit it with a sledgehammer of the same heft as your axe, but

there really is no substitution for actually putting axe to wood.

Kyle has

gone to the STIHL Timbersports World Championship almost half a dozen times now

with the New Zealand national team. The last few, in Europe, have been

literally on the opposite side of the world, and he is debating whether it is

worth it to go very many more times. He says there’s not as much exploring and

socializing as he would like, flying all the way out there, as the team trains

hard in the days leading up to the event, both off- and on-location, and then

they are usually whisked back home as soon as the closing ceremonies wrap. Kyle

talked about how he would like to extend the next such trip by another week or

so for sightseeing around the spectacular locations they like to host these

Championships in. The team relay tends to be on Saturday, however, and

especially for those who are not competing in Sunday’s individual championship

Saturday night is the time to cut loose, eat, drink, and be merry, hang out

with the collected best woodsmen in the world. Kiwis being among the best in

the world (3 out of 6 World team titles, 18 Individual titles since 1997) this

is usually a joyous time, but Kyle will speak bitterly of the 2014 Relay. The

Kiwis started off strong against the Hungarians, and ended up beating them by

14.5 seconds in an event that usually runs on the shy side of a minute total.

However, instant replay showed that the guy on stock saw, relatively new to the

discipline (Kyle was on H-chop that year), had only had seven of his requisite

eight fingers over the line centred on the top of the log when the starter’s

gun went off, one pointer finger hanging a few hairs too low. This mistake cost

the Kiwis a 15 second penalty, abruptly kicking them out of the bracket of 16 in

the first round by half a second in a year when there had been high

expectations that they could capture first place for the third time running.

This only goes to show how close everything is when you are competing at such a

high level, small things like a split-second timing mistake or a hard knot can

shift the balance against the best laid plans of mice and men.

Thank you, dear reader, for bearing with me through this exceptionally long blog post. I hope you learned something, or at least found it interesting; please feel free to leave me comments with your thoughts and any questions! Thanks again!

|

| This old rigger is no longer the sharp, shiny comp axe it once was, but it still serves a useful function. |